Half Life Missing Information

Joe Martin is a Half-Life 2 obsessive who often wells up with actual tears when he thinks of the content Valve cut during development. Imagine his joy at finding the Missing Information mod, which collects workable snippets from the stolen HL2 beta and assembles them into a Steam-compatible mod. Joe takes a look at the parts of HL2 Valve didn’t intend for us to see, and wonders if the game we got was the best it could have been.

The Borealis sits ominously in the water, sealing into place as the Arctic ice surrounds it. I climb the ladder on the side of the ship and greet the terse, moustachioed man who’s waiting for me. His name is Odell. He looks just like someone I used to know.

The half-life of a drug is the time taken for the plasma concentration of a drug to reduce to half its original value. Half-life is used to estimate how long it takes for a drug to be removed from your body. For example: The half-life of Ambien is about 2 hours. So if you take ambien after 2 hours the plasma concentration will be reduced to. Missing Information, shortened MI, is a single-player modification based on the cut content from the leaked Half-Life 2 Beta. The current version is 1.6. The first version, version 1.4, released in 2006, features the content shown at E3 2003, including 'Traptown' and the Hyperborea chapter.

Or, rather, there’s someone looks just like him. When Odell’s character was cut from the original version of HL2, his model was re-used for the role of Resistance leader Col. Odessa Cubbage. This is the Half-Life 2 that was never seen. Scraps taken from the leaked beta and E3 footage, crafted into a playable mod by the delightfully named team, Gabe’s Love Tub.

Odell and I move through the ship’s empty corridors and I can’t help noticing how old everything looks, how bland the art style is. Blunted orange hues sit against off-whites and steel-greys, with only the occasional emergency-red wallbox to brighten up the place. I open one and take the flare gun I find inside – a weapon cut from the final release.

“I’ve got an idea, Freeman,” Odell/Odessa says, sitting down. “You’ve got a gun, I’ve got a cigarette lighter. How about you take the lead?”

Alone, I move down empty, plain, shoulder-wide corridors, unable to shake the disappointment at how dull this has been so far. I’ve spent years fantasizing about what the Borealis might contain, going over and over the extracts contained in Raising The Bar – and a lonely, monotone boat is what greets me? Was this worth salvaging from the illegal betas and level fragments?

Up ahead is enough trouble to distract me for a while – a handful of Combine loitering purposelessly on deck in odd-coloured armour, carrying OCIW rifles I remember from screenshots of the leaked beta. I smother the soldiers in flarey flames and, when I’m done, there’s a litter of weapons left behind. Rifles, shotguns… and a fire extinguisher? I blast the smouldering corpses to no effect, move on, then return to try again and investigate if it has a secondary fire.

It doesn’t. Moving back down into the Borealis – which is called the Hyperborea in this map, but is identical to the point that the names are interchangeable – it strikes me that nothing seems to make sense. The Bridge leads down towards a meat locker, but there’s no kitchen in sight. There are zombies everywhere, but no bodies or headcrabs. The demented geography funnels me through engine rooms and cargo bays with no logic or pattern guiding the route.

Why the zombies and soldiers are here, I have no idea. The Borealis has existed in so many versions of HL2’s script that it’s impossible to know which one this is. The ship has been everything from the starting point of the game to a critical objective in its own right, but Odell didn’t give any reason for this visit in particular and there’s no clue in the environment, which is bland and inconsistently paced.

It’s not until I stumble into a couple of stalkers that I start to pay real attention. The stalkers, like the Borealis, were constantly cut back from their original outline, and felt under-used even when they finally stepped up in Episode One. Perhaps they are a chance for the Borealis to shine in my eyes? Instead though, without enough room to dodge their precise laser-beams, they feel like the lowest point yet.

Eventually I find Odell again – though I’m sure he must have noclipped his way through the ship to be able to get this far ahead. He leads me up to the deck where, hanging from the end of a crane, a submarine awaits us. He tells me this is the way out, and before I can even muster enough anger to hit Alt-F4, the screen fades to black and the main menu pops up.

I can’t believe it. All that expectation and…that was it?

Desperate for and convinced there’s more, I boot another of the standalone levels. The Borealis is nowhere in sight now; I’m back in City 17 instead. There’s open battle on the night-blanketed streets, ‘though I’m forced to stick to the rooftops and snipe manhacks out of the air through the OCIW’s sickly green scope.

The rooftop level is short and buggy to the extreme, but it’s still not all that different to the City 17 that was included in the finished game; same blocky architecture, same pastel textures. The mood has changed slightly though, and it’s not until I’ve cleared the first area of baddies that I realise why – this is the first time I’ve seen City 17 at night.

Viewed after sunset City 17 drifts an awful lot closer to the bleak dystopia that it was originally planned to convey. The Missing Information mod sadly doesn’t restore some of the more explicit attempts to capitalise on this – such as the Manhack Arcade where City 17’s gamers would unknowingly pilot Freeman’s foes – but there are hints to the overall tone. The Combine uniforms are more threatening for being re-done all in black, for example, while a different citizen uniform speaks to their own oppression.

Most of all the mix of enemies suggests a far more brutal, possibly desperate Combine force. Headcrabs, soldiers, striders and stalkers all mix together within a few hundred yards. Again, the stalkers prove to be the most annoying and it isn’t long before I pull down the console and look for a quicker weapon to kill them wi–

The selection of weapons fills the screen. Missing Information hasn’t just limited itself to adding fire extinguishers and assault rifles, it seems. There are AKs and Molotovs and SMGs. There’s a hopwire grenade which I can’t use without killing myself, the flamethrower that was supposed to be wielded by the lost Cremator enemy, and that tau cannon you always wished you could rip off the buggy. There’s even a huge ‘Combine Guard Gun’ which turns out to be the strider’s main cannon.

Once I’ve cleared my way past the stalkers, I try them all out on the remaining enemies. I start to really appreciate the way an old-fashioned AK-47 hints at an undersupplied rebel force, and the power of the knockback caused by charging the tau cannon.

But there’s something wrong, and I have to delve into the remaining levels – mostly restored versions of what was shown at E3 2003 – before I figure out what it is.

For starters, the variety that’s on show is simply too much. It feels like all the weapons of Borderlands have been dropped into a world and UI that were never designed for them. Trying to navigate the weapon list is impossible, while wielding mega-weapons like the strider cannon sucks the tension from the combat. What’s worst is the incredible overlap in ideas. There are three different types of assault rifle with under-barrel grenade launchers, two identical SMGs, three different melee weapons. They nearly all have alternate – or tertiary! – firing modes. It’s too much, too similar.

Compare that to what was eventually included in the finished game, where every gun was suited to a specific situation and I find it hard to look at Missing Information in the same way. It no longer feels like a memorial to the HL2 that might have been; it’s more like a graveyard full of ideas there’s no point pining over. All that time I spent pondering what the game might have been like has been a waste, because the value isn’t in the ideas themselves – it’s the refinement of them.

Guiltily, I thumb open my copy of Raising The Bar and take a fresh look at what lays inside. A quote from Gabe Newell’s foreword immediately pops out: “It doesn’t matter what we cut, so long as we cut it and it gives us the time to focus on other things, because any of the options will be bad unless they’re finished, and any of them will be good if they are finished.”

| Number of half-lives elapsed | Fraction remaining | Percentage remaining | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1⁄1 | 100 | |

| 1 | 1⁄2 | 50 | |

| 2 | 1⁄4 | 25 | |

| 3 | 1⁄8 | 12 | .5 |

| 4 | 1⁄16 | 6 | .25 |

| 5 | 1⁄32 | 3 | .125 |

| 6 | 1⁄64 | 1 | .563 |

| 7 | 1⁄128 | 0 | .781 |

| ... | ... | ... | |

| n | 1/2n | 100/2n | |

Half-life (symbol t1⁄2) is the time required for a quantity to reduce to half of its initial value. The term is commonly used in nuclear physics to describe how quickly unstable atoms undergo, or how long stable atoms survive, radioactive decay. The term is also used more generally to characterize any type of exponential or non-exponential decay. For example, the medical sciences refer to the biological half-life of drugs and other chemicals in the human body. The converse of half-life is doubling time.

The original term, half-life period, dating to Ernest Rutherford's discovery of the principle in 1907, was shortened to half-life in the early 1950s.[1] Rutherford applied the principle of a radioactive element's half-life to studies of age determination of rocks by measuring the decay period of radium to lead-206.

Half-life is constant over the lifetime of an exponentially decaying quantity, and it is a characteristic unit for the exponential decay equation. The accompanying table shows the reduction of a quantity as a function of the number of half-lives elapsed.

- 2Formulas for half-life in exponential decay

Probabilistic nature[edit]

A half-life usually describes the decay of discrete entities, such as radioactive atoms. In that case, it does not work to use the definition that states 'half-life is the time required for exactly half of the entities to decay'. For example, if there is just one radioactive atom, and its half-life is one second, there will not be 'half of an atom' left after one second.

Instead, the half-life is defined in terms of probability: 'Half-life is the time required for exactly half of the entities to decay on average'. In other words, the probability of a radioactive atom decaying within its half-life is 50%.

For example, the image on the right is a simulation of many identical atoms undergoing radioactive decay. Note that after one half-life there are not exactly one-half of the atoms remaining, only approximately, because of the random variation in the process. Nevertheless, when there are many identical atoms decaying (right boxes), the law of large numbers suggests that it is a very good approximation to say that half of the atoms remain after one half-life.

There are various simple exercises that demonstrate probabilistic decay, for example involving flipping coins or running a statistical computer program.[2][3][4]

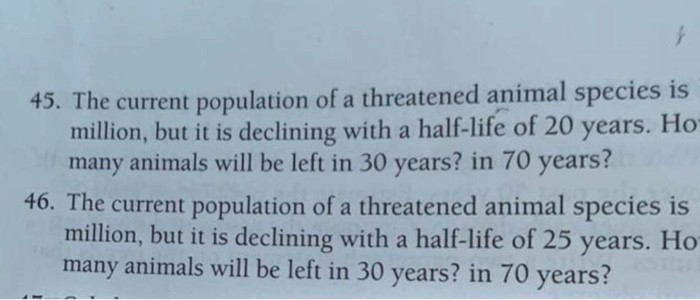

Formulas for half-life in exponential decay[edit]

An exponential decay can be described by any of the following three equivalent formulas:

where

- N0 is the initial quantity of the substance that will decay (this quantity may be measured in grams, moles, number of atoms, etc.),

- N(t) is the quantity that still remains and has not yet decayed after a time t,

- t1⁄2 is the half-life of the decaying quantity,

- τ is a positive number called the mean lifetime of the decaying quantity,

- λ is a positive number called the decay constant of the decaying quantity.

The three parameters t1⁄2, τ, and λ are all directly related in the following way:

where ln(2) is the natural logarithm of 2 (approximately 0.693).

Decay by two or more processes[edit]

Some quantities decay by two exponential-decay processes simultaneously. In this case, the actual half-life T1⁄2 can be related to the half-lives t1 and t2 that the quantity would have if each of the decay processes acted in isolation:

For three or more processes, the analogous formula is:

For a proof of these formulas, see Exponential decay § Decay by two or more processes.

Missing Information Download

Examples[edit]

There is a half-life describing any exponential-decay process. For example:

- As noted above, in radioactive decay the half-life is the length of time after which there is a 50% chance that an atom will have undergone nuclear decay. It varies depending on the atom type and isotope, and is usually determined experimentally. See List of nuclides.

- The current flowing through an RC circuit or RL circuit decays with a half-life of ln(2)RC or ln(2)L/R, respectively. For this example the term half time tends to be used, rather than 'half life', but they mean the same thing.

- In a chemical reaction, the half-life of a species is the time it takes for the concentration of that substance to fall to half of its initial value. In a first-order reaction the half-life of the reactant is ln(2)/λ, where λ is the reaction rate constant.

In non-exponential decay[edit]

The term 'half-life' is almost exclusively used for decay processes that are exponential (such as radioactive decay or the other examples above), or approximately exponential (such as biological half-life discussed below). In a decay process that is not even close to exponential, the half-life will change dramatically while the decay is happening. In this situation it is generally uncommon to talk about half-life in the first place, but sometimes people will describe the decay in terms of its 'first half-life', 'second half-life', etc., where the first half-life is defined as the time required for decay from the initial value to 50%, the second half-life is from 50% to 25%, and so on.[5]

In biology and pharmacology[edit]

A biological half-life or elimination half-life is the time it takes for a substance (drug, radioactive nuclide, or other) to lose one-half of its pharmacologic, physiologic, or radiological activity. In a medical context, the half-life may also describe the time that it takes for the concentration of a substance in blood plasma to reach one-half of its steady-state value (the 'plasma half-life').

The relationship between the biological and plasma half-lives of a substance can be complex, due to factors including accumulation in tissues, active metabolites, and receptor interactions.[6]

While a radioactive isotope decays almost perfectly according to so-called 'first order kinetics' where the rate constant is a fixed number, the elimination of a substance from a living organism usually follows more complex chemical kinetics.

For example, the biological half-life of water in a human being is about 9 to 10 days,[7] though this can be altered by behavior and various other conditions. The biological half-life of caesium in human beings is between one and four months.

The concept of a half-life has also been utilized for pesticides in plants,[8] and certain authors maintain that pesticide risk and impact assessment models rely on and are sensitive to information describing dissipation from plants.[9]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^John Ayto, 20th Century Words (1989), Cambridge University Press.

- ^Chivers, Sidney (March 16, 2003). 'Re: What happens durring half lifes [sic] when there is only one atom left?'. MADSCI.org.

- ^'Radioactive-Decay Model'. Exploratorium.edu. Retrieved 2012-04-25.

- ^Wallin, John (September 1996). 'Assignment #2: Data, Simulations, and Analytic Science in Decay'. Astro.GLU.edu. Archived from the original on 2011-09-29.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- ^Jonathan Crowe, Tony Bradshaw (2014). Chemistry for the Biosciences: The Essential Concepts. p. 568. ISBN9780199662883.CS1 maint: Uses authors parameter (link)

- ^Lin VW; Cardenas DD (2003). Spinal cord medicine. Demos Medical Publishing, LLC. p. 251. ISBN978-1-888799-61-3.

- ^Pang, Xiao-Feng (2014). Water: Molecular Structure and Properties. New Jersey: World Scientific. p. 451. ISBN9789814440424.

- ^Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (31 March 2015). 'Tebufenozide in the product Mimic 700 WP Insecticide, Mimic 240 SC Insecticide'. Australian Government. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ^Fantke, Peter; Gillespie, Brenda W.; Juraske, Ronnie; Jolliet, Olivier (11 July 2014). 'Estimating Half-Lives for Pesticide Dissipation from Plants'. Environmental Science & Technology. 48 (15): 8588–8602. Bibcode:2014EnST...48.8588F. doi:10.1021/es500434p. PMID24968074.

How To Install Half Life 2 Missing Information

External links[edit]

| Look up half-life in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Half times. |

- Nucleonica.net, Nuclear Science Portal

- Nucleonica.net, wiki: Decay Engine

- Bucknell.edu, System Dynamics – Time Constants

- [1] Researchers Nikhef and UvA measure slowest radioactive decay ever: Xe-124 with 18 billion trillion years.

- Subotex.com, Half-Life elimination of drugs in blood plasma – Simple Charting Tool